You won’t find a Lupe in my classroom. You won’t find a Felipe, Margarita, José, Rosa, or even Pedro. That’s because I don’t assign “Spanish names” to students in my Spanish class. So yes, I call on Dylan, Tiffany, Chad, Brett, and Brittany.

I don’t see the “appeal” of assigning fake names to my students. The first few years I taught, I started the program so students were not accustomed to having Spanish names. When I moved schools, students wondered why they no longer chose a name like they did the previous year.

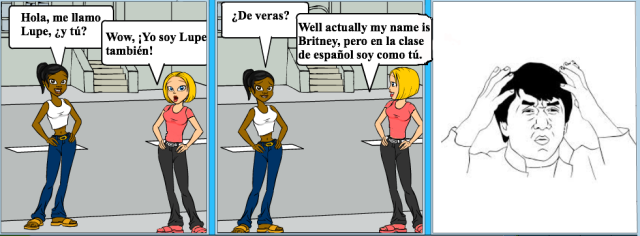

When students ask me, the conversation usually goes like this:

“Profe, why don’t we have Spanish names?”

“Do you have a ‘Math name’? Does your math teacher call you ‘Hypotenuse?”

“No.”

“Ok, then. When your Math teacher gives you a ‘math name’, and your History teacher gives you a ‘history name’, then I will give you a Spanish name”

I never understood the point of having a special name just for class. I guess my first reason was to make connections with the actual student. I remember when I was in high school I only shared Spanish class with certain students. I could tell you their Spanish name, but I had no idea what their actual name was. That just seemed odd to me.

Becoming a teacher, I didn’t want to memorize twice the number of names. Call it lazy, but when I meet Danny’s mom at conferences, I want to be sure I am talking about Danny and not Pepe. And just because they are speaking Spanish, doesn’t mean they need a new name. If students go to Mexico, people aren’t going to start calling them “Marta” instead of “Madison”.

I feel this perpetuates the notion that only some people are allowed to speak the language. “Tom” can’t speak Spanish, but “Juan” can. I want my students to know that ANYONE with any name can speak the language.

The point is, your name doesn’t have to be “Spanish sounding” in order for you to speak Spanish. Britney can be the name of a Spanish speaker. It is just another unnecessary stereotype that we perpetuate by saying that because you are speaking Spanish your name must be in Spanish too.

Some teachers will argue that having Spanish names is “fun.” Some say it helps students with pronunciation of authentic names. What do you think? Do you give your students Spanish names? It’s a worthwhile discussion to have as a department. If you decide to give Spanish names, I hope it is more than just because it is “fun”, “kids like it” or because it’s “always been done.” If those were acceptable reasons, wouldn’t every subject be choosing different names?

I agree with you. Well-written post, by the way; you eloquently state your point, and provide the rationale to support it. I especially like how you break it down to the students when they ask.

Honestly, I don’t think it’s something that language teachers give much thought to. They do it because, as you say, it’s “fun”, or, it’s the way things have always been done, without any intellectual rationale being applied. Besides, don’t we language teachers have enough work to do? Memorizing two sets of names? I’m not feeling that.

As a student, I always thought it was silly. And I never knew when I was being called on because I wasn’t used to responding to some strange name!

I give my students names only because I teach them Spanish from Kindergarten through 8th grade. I am the only Spanish teacher and they have me and I know them for nine years. SO I use their real names in class in Kindergarten, 1st and 2nd grade and then in 3rd grade….it is a REALLY big deal to them that they get to choose Spanish names in 3rd grade and they LOVE it. So by 3rd grade, I know them and their REAL names. Then I ask them through out the next five years if they want a Spanish name and they always do. Some really identify with the name they choose and keep it year after year after year and then others change their name each year. It is fun. But I have a very different teaching situation than you do. I understand why you would not have your students choose names so that you can REALLY get to know them and remember them.

I have been pondering this issue for the coming year. There are 3 reasons I have done it in the past: 1) introduction to cultural aspect of naming, 2) introduction to phonetics (there was a big to-do with a friend of mine calling a big-boned Jeffrey something too close to “hefty”–though I would say Yefri), and 3) when I made it a choice, 99% of the time, those who took a name did better, usually only those opting out failing. Of course there is no proof of causality, and really not taking a name was probably a symptom of something bigger.

TOTALLY Agree. I refused my ‘Spanish’ name when I was in HS and I don’t give them as a teacher. It is completely unrealistic. When I am traveling in a Spanish speaking country I don’t change my name. I understand why people do it (fun, cultural, etc.) but I feel it puts a barrier between the real students and the teacher. Whenever kids ask me about them, I explain that they have a name and I would like to learn it. I also have about 1/2 heritage speakers who have ‘Spanish’ names anyway. It just feels weird to re-name the anglo speakers and leave the other names alone. Teaching at a very culturally diverse school means that my students and I are exposed to many different and beautiful names from around the globe. I like it that way.

I totally agree with you!! It is twice the amount of work. The only time I did it it took all year to remember all of their names, memorizing 240 names instead of 120 was not fun at all; so I stopped giving names. What I did instead was, to translate just SOME names that were fun to translate. For example I had two students who their names were Jeremy and Zachary and I started calling them “Jeremias” and “Zacarias” by the time I got to know them, because they both rhymed, they thought it was funny and the class started calling them by those names. When other students wanted their names translated I just told them that it can’t be translated, because some really didn’t have a translation. Good Post!!

The following was written as a post on teachers.net regarding this topic.

On 8/16/11, Ashley wrote:

> I have had the students choose Spanish names for most of the years that

> I have taught. Yes it is a pain because it’s more names to learn, but

> the fact that the kids love it is enough reason for me. They think

> it’s tons of fun because they get to become someone else in a sense.

> And even when I run into them around town a few years later, I will

> call them by their Spanish name because that’s how I remember them.

> It’s a personal teaching preference, but there are lots of teaching

> aspects that come into play besides just choosing a name. So for my

> class, it makes sense as to why we might do that, as opposed to history

> or math.

My response was:

The only reason you gave was that the students “love it” and think it’s

“fun”. Wouldn’t the students also “love it” if it were done in History or

Math class too? I’m wondering what the reaction would be if other subjects

started doing this. I know it has been done for years and years in foreign

language classrooms, but the question is “Why?”. And does it benefit

student learning?

i allow students to choose their names, or keep their own, however, I warn them that in speaking the language their names may be enunciated differently to maintain the phonetic integrity that I am trying to instill in them.

I agree with Ashley. Some students really enjoy it. So make it optional after you have given them some examples of Spanish names. It does help with pronunciation, and is “fun”. Students do learn better if the class tone is fun, but no student should have to take a Spanish name if they don’t want to! I can’t believe this is being made into such a big deal! 🙂

I allow my students the choice to pick names. I teach in a mid-sized high school and since everyone knows everyone else’s name, for the most part, this is a fun way to practice those early questions of introduction. Many students wouldn’t actually need to ask any of their classmates what their names were but for this practice of having a new name in class.

Really great comment from “John” from http://teachers.net/mentors/spanish/posts.html

“I have never given my students Spanish names, nor will I do so in the

future. The simple reason for this is that they (in 99% if the cases) are

not Hispanic, and I don’t feel it would be right to pretend that they are.

If I were to go to Spain, Mexico, the Dominican, or wherever I would not

expect to be called “Juan.” I am not Hispanic; my name is John. Period. I

also do not wish to be called “Señor” in school for the same reason. I am

not Hispanic, and I don’t pretend to be. Save the “señores” for those who

are. I am a teacher of Spanish, not a Spanish teacher.”

way to immerse yourself in the language and culture, NOT, Maybe you should be a teacher of students…to each their own.

As a beginning teacher, I did this because every Spanish teacher I knew also did it. I never ended up learning many of them, and there was always that student who would pick a name even I had trouble pronouncing. Ugh! No more Spanish names for my students! Thanks for the great explanation of why not! Also, I would love to hear that someone is named hypotenuse in math class! hahaha

¡Qué cosa más rara! Yo soy una profesora de español en Suecia y a mis alumnos los llamo por su nombre y ya. No veo el motivo por el cual tener nombres ficticios. Lo único que suelo hacer es decirles como sonarían sus nombres en español. Claro, siempre y cuando fuese posible.

I loved this post! During my first 4 years of teaching Spanish, I let the kids choose a Spanish name. They were always confused…they didn’t know when I was calling on them; they couldn’t remember their friends’ Spanish names; they were constantly asking which name to put on their papers. I always felt like I had to know both of their names, which was difficult with the number of students we have in our classes. This is the first year I haven’t done Spanish names, and I am LOVING the results. I feel like I can connect better with my students when I can use their own given name. I’ll never go back to the old way!!

Thank you!!!

I have such a hard time remembering the English names, let alone Spanish ones. I haven’t officially had my own classroom yet (only student teaching and long-term subbing) so I don’t have a choice yet, but when I have my own room….

Where did this tradition come from anyway? I’ve never understood it! I teach University level Spanish so we would never give them fake names at that level anyway, but if I tried, they would all think I was crazy! I remember thinking it was fun for about two days in Spanish class in HS. Then it kind of annoyed me. I even had one teacher make fun of a friend of mine because she couldn’t pronounce the name she had picked out for herself correctly. What?! This is supposed to be FUN! Not make the students feel badly about themselves!!! Keep on not giving out names. It’s better in the end!

I have always let students pick Spanish names. Why? Because I loved being “Alfonso” in high school 15 years ago. It was a great alter ego. However, I understand that some kids are very proud of their names and don’t want another name, so I let them know I’ll do my best to pronounce their name but it’s going to be with a Spanish accent, just like when I am in central America most people call me “Yon” instead of “Jon.” I think it’s a fun tradition that it lets kids know that in THIS class things are different. In Spanish class we speak Spanish and have names that are Spanish. It doesn’t need to be a negative issue and it’s easy to remember the names if students are only allowed to choose Spanish names that are similar to their own name or at least start with the same letter. I think I will continue this tradition but I appreciate all the different viewpoint and I will not be annoyed if other teacher’s don’t use Spanish names. I do remember though one student who came to tell me he was sad his new teacher wasn’t calling him “Benito” but just Ben. He felt it was weird that this teacher didn’t even address him in Spanish, much less acknowledge that he liked his Spanish name.

awesome reply! estoy de acuerdo!

YES! Thank you!

Totally agree!! I do the same, allow the students a choice and create a cultural atmosphere. After all, my class IS different! I’m conveying a culture (many cultures) while teaching Spanish, unlike math or science. It obviously wouldn’t make sense to choose math names because those terms aren’t human names. But in Spanish I attempt to create the culture as best as possible in the classroom. And if students enjoy it and it’s part of a positive environment, then I see no reason why not. We live the culture as opposed to only learning about the culture.

I agree with you, this is just about me being able to remember some of their names. With my heavy Spanish accent, I know that I will be saying their names wrong and they will be trying to correct me. Therefore, I offered Spanish names, some of them accepted, some did not and after all, it is well with my soul and memory! Thanks for your input!

Totally agree! My kids like it and it isn’t forced. I learn their real and Spanish names, so there is never any confusion. It just sets a tone that in here, I am me but I’m developing this secondary identity in Spanish. To learn a language is to develop another identity.

Yes, I do – in kindergarten because most of them think it’s part of the “magic” of an immersion Spanish class. It helps create a “this world is different” atmosphere. Their classroom teachers speak to them in English and give them worksheets and homework and make them walk in a straight line to the bathroom. This is not my world. My world is different. My world is Spanish world. Sometimes (two or three last year, I think) a student told me they didn’t like to be called something else, and I immediately switched to their given name.

In high school, I only do it if they ask for one in particular. Usually there’s a story behind it. One student named Christian somehow got the nickname “Coffee for one” which he translated “Café de uno” and wanted everyone to call him that – in Spanish class and out. Last year Oakley wanted to be called Roble because it was the Spanish word for oak, and everyone called Paige ‘página’ for obvious reasons, which she thought was funny, and so sometimes I did too. I called Logan “LoGÁN” because he was interminably mispronouncing the Spanish A. In that way, for my older kids, it’s more like a nickname for Spanish class than a Spanish name.

I couldn’t agree more. What does a Spanish speaker look like? Sound like? I speak Spanish and I don’t have a Spanish name. Why do we assume that every Spanish speaker will be called Jesus or Maria? Thank you for posting, I have never believed in giving my students “spanish names.”

Agreed! I teach French at the university level and my students always arrive and say “Hey, why don’t we choose French names?” I don’t have the time to memorize multiple sets of names for multiple classes. They are not French or Francophone. I’ll pronounce their names as they would be in the French language to help with accents, but no names. “What if I want a French name?” usually gets the response “You can call yourself Thierry if you want, but I’m still going to call you Billy.”

I never liked having a “French” name (it was usually Paulette) in class, and it sure didn’t prepare me for learning to pronounce my real name in French once I actually spent time in France, and learning that it sounded amusing to French-speakers — poli!

Besides, what is a “real” French name, for example, is culturally and socially a bit outdated these days. N’est-ce pas?

I agree. Granted, I teach college, so giving students a French name is a bit less common at that level (though I still have students ask me if they will get French names). My reasoning is that it creates one more barrier to authenticity in the classroom — as though French were just a play-language that we only use in the land of make-believe. If I want my students to engage with the language and imagine themselves using it in their lives, giving them a fake identity is not the right way to start — fun though it may be.

I teach first year Spanish (and used to teach French I-IV). I always enjoyed choosing my name in high school French and Spanish classes because I’m not particularly fond of my English name. I don’t know why, but I never expected to continue using foreign names when I went to college.

This is my eleventh year of teaching and I still plan to allow my students to choose a name although I’ve noticed a drop in students’ willingness to embrace their names. My students used to have fun choosing them, calling on classmates, and telling me they put their foreign name on their science homework; not so much anymore.

So why continue then? Because some still embrace it, or at least tolerate it. I also introduce it to them as a way to get their brain into Spanish mode. Finally, I do it for my sanity. I have few problems learning their English first and last names as well as their Spanish first names. Don’t get me wrong, there are always a couple each year that I struggle with, but I eventually get it. I allow them to choose ANY name with a couple of rules. If it’s close to their English and they want it, they have dibs. Otherwise they can take ANY name with one other stipulation — no repeats within their class. This eliminates the problem of having Brittany, Britney, and Brittnie in the same class or Casey and Kasey, one a boy and one a girl. So yes, I have to learn extra names but in the long run it makes it easier to address students in class. After the first few weeks I am always able to address my students by both their English and Spanish names, even if it takes me a second to switch gears.

When I taught upper level French classes, picking a name was always something the kids looked forward to because I would allow them to choose anything they wanted. I’ve had students named “Toe,” “Bush,” “Grapefruit,” “Woof-woof,” “Squirrel,” and because she figured it out on her own I even had a “Bite me”!

I tell my students I will give them a Spanish name IF THEY WANT ONE. Some students actually enjoy having a “Spanish” name, so why not? If you’re speaking entirely in Spanish,it does flow more naturally to say “Susana” than “Susan”! Everyone makes a “name card” the first day of class to put on the front of their desk, which makes it much easier for me to learn 30 names!

You make good points. For those who insist on giving names, like me, I just tell kids to choose the closest equivalent from the list I give them. A lot of them buy into that and they don’t choose a name that is far from their real one. If they don’t like the equivalent, I let them choose what they want. It really isn’t a big deal to me even though I have to learn twice the names. I get them eventually.

You could make the same argument for asking for permission to do things in the TL. For example, Est-ce que je peux aller aux toilettes? It’s true that you’ll probably never have to ask that, even with a host family. However, in class, it sends a message that you’re interested in them communicating in French and admins like and expect kids to be able to say that.

I do wonder when and why this tradition started though. Other countries don’t seem to do when they are learning another language.

I agree, spanishplans. How did this tradition begin? A bizarre one, I think.

I teach French and I NEVER give a French name. I find it so strange, you don’t get to really know that student if you don’t even refer to him/her by their given name. And in France, if your name is “Amy” they will call you “Aimee” , if your name is “John” they will call you “Jean”. If your name is “Madison”, they will call you “Madison” with a french accent. I want to give students a REAL experience, not a fantasy one that would never exist in real life.

I find this topic interesting. I have been teaching Spanish for almost 30 years. I have always given my students Spanish names. Teaching Spanish in America is an artificial situation to begin with. In many neighborhoods, students speak English, not Spanish. I give them names so that we can create a scenario where Spanish is spoken. We do a lot of things that students wouldn’t do in “real life”. We ask them to speak in Spanish for simple things, like going to the bathroom, sharpening their pencil… do they ask to go to the restroom in “math” language? It is easier to speak without changing to English to say students names. For high school students, I let them choose animal, plant or adjectives to use as names. This widens their vocabulary. Now, in MS, i give them a name that begins with the letter of their first name. If there are repeats, they pick a different name. Learning Spanish, French, Italian, Chinese, is a fantasy for them, is that so wrong?

Thank you, Doug – a great response! 🙂

I’ve been teaching French for 38 years. My basic premise is to pronounce the names “the French way”. If there is a name like Bryan, I don’t want to say “brilliant” each time I call on him, so then I go to the middle name. For repeat names, I try to call one of the students by a hyphenated name using first and middle together. If a student wants to change his name, I let him, too. I like this topic..

I think in France one would insist on pronouncing it Br-EYE-ann. Anyway, here’s a shot of how many French Bryans there are in France lately. And this name website is a good indicator of how French names are changing. Not just Jean and Pierre anymore!

http://www.aufeminin.com/w/prenom/p2941/bryan.html

This is a great discussion. It is fascinating to see the different perspectives; it does seem that the level at which you teach has a great affect upon what you choose to do.

I have been teaching for almost 20 years, the last 15 teaching K-4 Spanish at our local elementary school. Little kids love to fantasize, play pretend, and are very interested in, and excited about make believe. As they get older, this changes and is funneled into other energies. I think this is part of why we elementary teachers give “Spanish names”, whereas teachers of older students may not. We are still playing with puppets who talk and take trips and send postcards, weaving our imagination into our language use on a daily basis.

I do give Spanish names to my students; however, I don’t do this until Second Grade (we start in Kindergarten). My students are extremely excited to get their “names”, and ask me repeatedly in Kindergarten and First Grade when they are going to get them. However, before they get the names, we have a discussion about what a name is, and what having a ‘Spanish name’ means. I explain this is just for fun in class, but that we all know their real names, which would be used whenever they were with anyone else. Most kiddos understand this difference. (And since I wait until 2nd grade, I know their given names long before the “Spanish names” come along)

I will add that my Spanish and Russian friends ( I speak both, my native language being English) all have “Spanish” or “Russian” names for me… Ju, Julita, Julieta, Yuliya, Yulichka and so on. I find that endearing and very touching.

Julie

I always liked having French and Spanish names in my high school classes. It helped me get into the mindset of the language, and I did – do – feel like a slightly different person when speaking them. In college and beyond, though, it would feel silly.

This is precisely why I also give Spanish names in class. When you speak another language, you are getting into a new persona. Having a new name is part of creating a mindset. My classroom is literally a classroom, however, we imagine ourselves all over the world. It helps students “get out of themselves”. Psychologically, the willingness to “let go of self identify” and take on a new persona is one of the theories as to why some language learners have difficulty taking on a native accent. When I speak Spanish, I feel a different area of my brain working. I feel I am a different person, much like playing a character in a play. People I know, who don’t usually hear me speak Spanish, are surprised when they hear me. They say I actually have different voice.

Hola- I love reading your posts on this topic. This is my 10th year teaching Spanish and for the first 7 years I never did this and thought that it was a silly tradition. When I changed districts- all my new colleagues did this, so I thought I’d give it a try. Their rationale was that when the students come into class that they have a new identity and that they are in a new world. I tried it and the students really did love it. Being Colombian, I know that if they went there that people would most likely not change their name unless it was something like John- Juan, Michael- Miguel but they liked it and I had no problem remember both names- maybe this will change in a few years- who knows.

Now, regarding the topic of the students calling you Señor, I have to respectfully disagree. Even though you are not Hispanic, they are learning how to address an adult in a formal situation and if you went to a Spanish-speaking country they would call you Señor – no?

I agree with you. In any Spanish speaking country people would be called Señor or Señora. It is the polite way.

Agreed. “Señor” is a title, not a name.

Hello! I do use Spanish names in my classes, but I don’t have a problem if another teacher chooses not to. My Spanish and French teachers in junior high and high school used them. My college profs did not. When I began teaching, I thought about it and made a conscious decision to use them. Here are the reasons I do:

1. My name is Sharron. It is hard for Spanish-speakers to pronounce. I often go by Sarón when traveling, especially if I am working with children. It is easier for them to say, and it is the word used in the Spanish Bible where the English Bible uses Sharon (a place name). Not a commonly used name in the Hispanic world, but easier to pronounce. Likewise, my friend Keith goes by Roberto. I think his middle name may be Robert.

2. My students struggle with overcoming English pronunciation. By using Spanish names in class, no one has to remember to switch back and forth between the sounds. We walk in the room and use Spanish sounds, except for the times we intentionally switch to English. Hm…perhaps I should intentionally switch and use their English names during that time, too. Hadn’t considered that.

3. I do not assign names; my students choose them. I tell them, “Your parents gave you your first name–you had no choice. Now, for my class, you get to choose your name. You can choose something similar or something completely different. You may change your mind during the first two weeks of class, but after that you keep the name for the rest of the year. If you want to change next year, you will have the same two weeks to make up your mind.” Many of my students use the same name year after year. Others change it up. By third year, for most it has become a part of their identity like anything else about them, as has their blossoming skill in using the language.

I think it is very ethnocentric to believe there is such thing as a “Spanish” name. Of course there are names that are ethnically Spaniard but the vast majority of our “Latino or Hispanic” students (whatever label you chose to give students whose L1 may be either English or Spanish, may be first or second or third generation and have one or both parents of Latin origin) are not Spaniard ethnically. They are diverse and so are all of our students. Names are no longer tied to distinct ethnicity or language…just look at the number of Asian Molly’s or Michelle’s. “Foreign” names should not have to be converted to “American” names (whatever that crap means…I don’t see many Koreans choosing Little Feather-truly American of course..)and our students with non-Latino/Hispanic/Spaniard names should not be choosing a name to use in Spanish class. It is really against most of what we do and know as educators.

I do let them choose Spanish names OR keep their English name (they 100% have the option and usually it’s about a 75/25 Spanish name/regular name split). My name is Nicole and a lot of times when I am living abroad (like I am right now), my friends, professors, etc. start calling me Nicoleta or Nico-le (two syllables) because Nicole just sounds weird in Spanish. I also KNOW that I change as a person when I live in a Spanish speaking country. Our content area is so closely associated with the cultures and countries and peoples, and it extends so far outside the classroom. In HS I LOVED stepping into class and knew that everything was different from the rest of my day — my teachers created a Spanish-speaking world inside the classroom and with that came our different identities. I strongly believe that having a Spanish name made me connect with the culture more strongly, which is why I give my students a choice. Additionally, the list I provide for them to choose from is not an exclusive one — if they have another name they’ve heard I usually let them go with it.

I give the students the option of choosing a name…but they don’t have to, nor do they have to use it once they have chosen one. (They can’t however, CHANGE names). They can use the Spanish name or their given name-the choice is theirs. I don’t really care, but I tell them that when I am speaking Spanish their name may be pronounced differently than they are accustomed to hearing it, due to the different phonics.

BUT, who began the “fiesta” days in Spanish classes? No other content area seems to have this issue, I am new in a district where students expect them and parents complain about them!…just sayin’ 🙂

Agreed! Fiesta days are more of a pain for me than choosing new names.

Ya, I think you put it best when you said you were lazy

I let them choose one for fun and i have them call me señora. I think its fun and helps me develop a relationship with the kids. If they pick something far off from their given name I like to find out why. As my students get to their third and fourth year with me I usually have a new nickname for them that has to do with a personality trait or an inside joke. Last year in my upper level classes I had Ricky Rubio, Viktor Cruz, Calabaza, Gato, and more. I think it helps them feel closer to me and the rest of the class because this alter ego is a side that they only share in my class. I do explain to them that names don’t necessarily translate and that there are Spanish speakers named John. There is no one correct way to teach language and teachers have to go with what they feel comfortable with.

Your method also reveals to students a cultural tradition in Mexico where people are given nicknames, apodos, I love it!

I agree with you. I don’t force names. Some choose to not have another name, but some really want a nickname..so why not. They learn a little more vocabulary with it and have fun with it.

I’ve never learned Spanish, but I have studied both German and Chinese, as well as taught German and English. Aside from languages with different writing systems, where you have to choose an equivalent simply so you will be able to write your name, I always thought the idea of choosing a different name for a language class seemed kind of silly. None of my German teachers ever did it, and I have never done it in my classes. Even though I’ve had a German name for ten years (I’ll explain that below), I never wanted to use it in class. And I would have felt like an idiot (and kind of an imperialist) trying to give my Saudi students American names. I just had to struggle through learning to distinguish all the Mohammeds, and getting made fun of for my pronunciation. But it was a learning experience for all of us, and I think one worth having.

That being said, I also work at Concordia Language Villages, a summer immersion camp where the kids spend 2-4 weeks with us. They choose new names, and I fully support that. To represent major immigrant populations, we include a number of Turkish and African names as options in addition to typical German names. Some of them stick with their real name (assuming it’s culturally appropriate), while others go for something completely different. Some kids stick with the same name for ten years, while others change it every year. In the context of the camp, we never use the kids’ real names, except on final evaluations, where they are already written for us, including the camp name. Because they spend an extended period of time with us, and we attempt to create the culture around them, a lot of them see their new name as an opportunity for a new identity. I know my camp self is very different from my “real world” self (the counselors and teachers have camp names too). For kids who return year after year, their camp self becomes so important to them that many of them include their camp name on facebook!

I read this post when it first came out and it opened my eyes! What a blessing it has been to not have to learn “English” AND “Spanish” names at the beginning of the year. You have alleviated so much stress in my life. ¡Mil gracias!

Glad it provided you a new outlook!

Muy buen punto. Es algo que yo nunca hacía, hasta hace cuatro años atrás. Trabajo en una comunidad nada diversa y al ver el entusiasmo con que escogían sus nombres, pues decidí hacerlo. Sí, es más trabajo pero tengo buena memoria así que no me molesta recordar la doble cantidad de nombres. Les gusta un montón y aprenden a pronunciar nombres en español y los míos nunca han tenido problema recordando los nombres de sus compañeros de clase.

Students love it. That’s all that matters.

I understand where you are coming from, but I think you have to look at this from a non- native speaker’s perspective. Lucky for you, I am not a native speaker:) I do allow my students to pick a “Spanish” name after a couple months so that I won’t forget who they truly are. Some want to keep their own name and that is fine with me too. Not only does it help them learn some common names in Spanish speaking countries and how to prononce them, some of them just get the biggest kick out of it. They’re learning culture and they’re having fun. I’ve even had students create twitter accounts using their Spanish name! I can’t tell you how many times students have asked me “Is this word a name?” when translating. I’ve had students not know José or Juan was spelled with a “J”! Some people like me (Heather) and my husband (Quinton) have names that are difficult to pronounce for our Spanish speaking friends so I don’t agree with you that people are going to stop calling you by your name. Our Spanish speaking friends have renamed us both because of the diffculty of our names for them, but we are ok with this because they are our friends and they have their own terms of endearment for us! When I first started going on missions trips after just having a few Spanish classes it was so difficult for me to remember peoples’ names because every name was so different from what I was used to at home. My hope is that exposure to common names will help them remember them with more ease when they meet Spanish speakers who have the names we’ve used in class. To each his own. I enjoy your ideas so much.¡ Gracias!

Thanks for sharing your perspective! Definitely something that new teachers need to consider, so it’s good to hear both sides. It’s good to read your specific reasons for choosing to do it! Thanks for commenting!

I don’t think it’s too much more work, I just naturally learn both names (and last names) easily each year since I call on them by name and move their seating charts regularly (I have 150 students). I disagree that using “Spanish” names creates a disconnect, in fact I think it does the exact opposite. It creates something in common with the students around them, whom they maybe otherwise wouldn’t talk to outside of class, giving them an ice breaker (saying, “¡Hola Juan!”). I feel it does the same between the students and teacher too.

Furthermore, I feel that it’s kind of like nails on a chalkboard to use “regular” names in the middle of a Spanish sentence. Everything flows better when they’re using Spanish names, and it helps them remember rules for sounds. Also, chances are they’ll eventually meet someone named “Miguel, Javier,” etc, and they’ll know how to properly pronounce it, instead of sounding like a fool since they never learned something so basic in a language class.

No need to be so serious, Betty. I give my student a list of Spanish names, and then say that those who WANT to choose one, can. Otherwise, they use their real name. There are always a few who prefer a Spanish name, for whatever reason!

I totally agree. If a parent named their child a name then THAT’S their name. I have no right to change it. Secondly, why does it have to “sound spanish”? I totally have a student who came from Mexico and his name is Jake. Thats right, Jake. I have another named Jay. It is what it is. This issue has bothered me especially when I read the book Amazing Grace in its Spanish version. It’s called LA asombrosa Graciela. I don’t understand why you would go ahead and assign a Spanish version, supposedly, of a proper name. We don’t do that to food chains like Wendy’s or McDonalds but it’s OK for people?

Probably from the invaded parts of Mexico, sadly. Or when they travel to the USA they want their kids to “assimilate,” though I don’t know why since the first European language was Spanish. You don’t do it for Wendy’s and McDonald’s because they are corporations. It’s called Trademark. Movie titles and fictional characters are different.

I just got a Spanish name in my college Spanish class after having taken 3 years of Spanish in high school and being called “Maria” when my name is “Hayley” bothers me. It makes me so uncomfortable because it’s like they stripped me of my name. I hate it. I’m not this other identity, I’m me, trying to learn another language.

Czech proverb – Learn a new language, get a new soul.

As I shy Anglo, I identify with this when I’m speaking Spanish. I like the flow of the language when my students have Spanish sounding names, but more than that, I want them to find their Spanish personality…their new soul.

Just a note… my name may not actually change when I travel, but I AM called Nicola instead of Nicole when I’m in Spain or Italy.

Definitely agree that if your name has a similar sounding version in the other language it is very common to be called that. John to Juan, Mary to Maria, etc. Students like to hear what their name *would be* in another country. Likewise, pronouncing a students name as it would be pronounced in the target language is also very meaningful.

These are very distinct scenarios than making a completely different name; for example changing your name from Brittany to Margarita.

My friend has an Argentine mom and they named her Nicole, but her mom still calls her Nicola! I completely agree with you, though I had not consciously thought about it. Since I got to college and my Spanish abilities improved enough to make conversation/read/write/listen better, I honestly feel like I’m another person when speaking Spanish. And being around native speakers more, I have adapted/changed some personality and lifestyle traits – I will gladly engage conversation with native speakers I find at the store (rural area with not much diversity so you can imagine my enthusiasm and theirs as well) but cannot stand/avoid making conversation with Anglos. My Spanish self is somewhat more obnoxious/outgoing (which isn’t saying a lot, but there is still a difference), I will be a little more blunt/vulgar in Spanish than in English, depending on the participants, obviously.

I think it’s just a great way for students to explore the language and culture, as long as we remember to mention that Hispanic culture also has “regular” English names as well 🙂

Pingback: Top 5 Reasons for and against Spanish names | SpanishPlans.org

I don’t give Spanish names to my students for two reasons:

First, It is very difficult for me to memorize 100 plus names. It creates confusion.

Second, students should know how their names are pronounced in Spanish. This important is important when they are traveling or being called by a Hispanic, they will know how it will be sound. Most likely their names are not going to be pronounced with an American accent.

I would have sued you for discrimination. Or told my parents to do so for discriminating against them. These students were raised by them not you. What you are doing is forcing your “Manifest Destiny” onto your students and whitewashing their history and culture. Are you aware that the first European language spoken in the “USA” was Spanish? All of the Spanish-speaking teachers not native speakers have come up with batshit-crazy idea that your name automatically changes when traveling/going to predominantly Spanish speaking places. If you go Mexico and your name is Madison, you will be called Madison! My foreign language teachers never did that bullshit. Respect their names.

You can disregard this post. I thought you were teaching Spanish to native Spanish speakers with basic knowledge of their language when you used “Señor.” I originally didn’t see the images you posted.

I am so glad to have found this post and these comments! This is my fourth year teaching Spanish and the first that I’ve not given my students Spanish names. I find it to be culturally insensitive. When they ask, I say, “And what list would we give to students learning English? John, Jimmy, Susie? How do we decide which names “represent our culture?” I have many former students from my days as an ESL teacher and friends in Spain who are all native Spanish speakers, and their names are across the board.

And as a teacher with 120 students each semester, there’s no way I’d be able to learn their given names and their Spanish names. When I run into them outside of school, I want to know who they are. When the guidance counselor or their parents email me, I want to know who they are. When they reach out to me years down the road, I want to know who they are. And I don’t want them having to pick a new Spanish name each year because someone in their class is already Ana or José.

Thank you again for this!

I always liked my Spanish name, it is just a Spanish translation of my name which I thought was cool, when I visited Mexico I went by my Spanish translation of my name. It was still MY name but just translated in Spanish. I respect that others have opinions on this that differ and I respect the teachers right to choose what to do. I understand there may be some names that may not have a clear translation.

If a student’s name is a direct translation (John =Juan or Anne =Ana) then I use them. I also explain they dont change names for real when they cross a border. On the other hand I end up “Spanishizing” the names because that is what many native speakers do! I was married to a Mexican for 6 years and being Hispanic I have been involved in the local Hispanic/Latino culture most of my life. Almost without exception if I introduce myself with the English pronounciation Eleanor, someone who is very fresh to the states/doesnt speak much English has a hard time “catching” my name. When i revert to Spanish pronounciation of Leonor, they “catch” it. Even my own (ex)husband never said Eleanor, he called me Leo. So if I have a Madison I end up naturally calling on “Mahdeesohn” using the Spanish vowels.

Funny to add, I worked as a linguist briefly for “Obamacare” and a coworker from Colombia had the name John, not Juan. I heard him have to explain over and over to native sp on the other end that he was “John, como Juan”. In that same situation I also introduced myself as “Leonor” because it just made my life a lot easier.

I’ve been teaching since 1982, and I used to have students create an entire alter-ego from the culture they were learning. I had lists (huge lists!) of traditional first and last names, cities, and professions, and they would create a persona and story for this person. Now I no longer do this. My students have come to my class with French or Spanish names from previous years, and I just call them by their own names. Why? Several reasons. 1. My name is Debra, and one French teacher once told me that wasn’t a “French” name, and so I had to be Dorothée. Yuck! Odd, since I grew up speaking French and was baptized Marie-Debra. 2. A high school student once told me her mom had met her French teacher in the grocery store, but the teacher didn’t know who the mom was talking about, because she didn’t know her real name. 3. Every year I teach, the time it takes me to learn the names of my students becomes longer. No way I’m learning twice as many. 4. Kids ask me what their names would be in French or Spanish. Some kids don’t have translatable names, and I tell them that no matter where they go, their name is whatever their name is. Former King Juan Carlos would not become John Charles if he came to the states!

I agree in not giving Spanish names to students, their name is their own. They were given that name, whether is Jason, Jeison, John or Juan, it’s their name. As their teacher I want them to embrace their name that their family chose for them. I go so far to properly pronounce their name (for those difficult ones to say), as that is what expect from them to me. My last name for some is difficult to say and in Spanish it means a part of the body. But I make it clear what my name is, how it’s pronounced, and show my Spanish speakers I am aware of what it means in English (but that is not my name). And it’s too many names to learn if you have to learn another 200+ Spanish class names.

I totally agree with this article. As an ESL teacher and a Spanish teacher, I refuse to “Christian” their names or force them to choose a Spanish name. I get really angry at my fellow ESL teachers who do so. Even my co-workers change their names to make them easier for Americans. I always ask, “What does your mother or native language friends call you?”

I let them choose names because I can pronounce correctly their Spanish names,as opposed to the roster of real names that I invariably massacre every time I try to take attendance.

Thank you. I didn’t realize this was even happening. My name is Wendy. That’s not an “Americanized” form of my given name. That IS my name. My parents both came from Cuba and I am a first generation American. It’s insulting to force a “Spanish-ification” of a given name on a child in order to learn a language. It’s also giving the misinformation that in order to be a true hispanic or latina that I must have a “Spanishified” first name. I’m also a teacher. I don’t Americanize my students’ names either. If your name is Piyawut, then that’s what I’ll call you. I won’t change your name to Pete just to make it easier on me or just because I am now teaching you English.

Finally someone agrees with me. 😁 I also, do not give Spanish names. One I want my students to understand that they do not have to be Spanish in order to speak the language and two I have no time to memorize 150 students name plus Spanish names. Thanks for the read.

I do it to simulate immersion, so students feel transported out of Kansas. I also want them to feel like a different person when they’re in our class, someone who speaks Spanish.

Why can’t they speak Spanish as themselves?

Thank you for writing this article. I never understood the assignment of “language names” in class. I teach German and do not give my students a German name. I don’t even know what that means anymore. German is multicultural. The whole world is. And for me it was always a bit limiting and culturally discriminating. And to remember twice as many names is just plain exhausting. I want to get to know my students as soon as possible, so that I can help them learn. Maybe I am afraid that I will never know them by their real name and will blank out when other teachers talk about them, lol.

I ask the students if they want a Spanish name. If they do, they can pick one at the beginning of the year. It helps them with their pronunciation and I think they find it fun. I think it will also come in handy for them in real world situations. If they ever do have a Spanish speaking experience, it will be easier for them to introduce themselves using the Spanish names. I also think it’s useful for their Spanish pronunciation practice, and hearing my pronunciation of the names as well. Anything I can do to make the class more “real world” and fun. I will do.

What’s “real world” about it if they are “fake names”? Would they actually introduce themselves as Pepe as opposed to Steve?

I think it’s good exposure to different names they may not hear in their normal day to day, increasing cultural awareness. It also helps with reading comprehension. For example, one time I had a student ask me what a Spanish word meant in his reading, because the sentence didn’t make any sense. Turns out the word was a name he had never heard before (I hadn’t given them Spanish names at that point) and he didn’t understand the word was a name given the context.

Both my children Isabella Natalia Rodriguez and Alexander Rodriguez had to pick Spanish names although they were Spanish and had names. My name is Swedish and I’m Spanish.

I agree it’s closed minded and creates stereotypes. How much more Spanish can my kids names be you ask? My son is now Pedro Felipe in Spanish class. HE Couldn’t keep his real Spanish name,notspanish enough. It’s ridiculous and I’m glad other people agree. I think it is cultural appropriation and perpetuates Spanish stereotypes. We have Lincoln’s, Rene’s, Alex, Ana, Bellas, Alícia, Marco, Jonathan, and Lupe and Pedro. So in English class should we be called Angus, Atticus and Claire. Will that help us understand better. I know some of those names that are Spanish as well. In today’s world it is backwards and perpetuates the notion that speaking another language or coming from another culture makes people separate and its so different from us we need a new name to exist in that world instead of Greg, Mary and Frank you can speak and or be Spanish too no matter what your name or color. You are just a person with a name who happens to speak Spanish and Engllish.

I am so glad I found this post! I swear I thought I was the only one left who does NOT give Spanish names. My classes are huge and the last thing I want to do is learn their 1st name, last name, and a second name used just for Spanish class. When I was in high school, my teacher called me Marisa, and although it was fun, I’m pretty sure she never knew my real name was Tara. 🙂 I feel it is important to address our students by names, their real names. The last thing I want them to do is pretend they are someone they aren’t, especially when teens today struggle to “find themselves” on a daily basis, more so now than ever! Thank you! 🙂

I allow my students to pick. When I was in HS, we all found it to be fun and exciting – I am from a small rural area and I teach in the same area although not my own HS. This is about as much culture many of the kids will be exposed to, if they want a name, I let them.

That being said, I have many native speaker friends and now relatives (through my honduran husband) who have names on Facebook that are COMPLETELY different from their real names. Why? We (my husband and I) have no idea. Because they like the name, we suppose. You can imagine my surprise when I got a friend request from Azul —- but I (and other family members) knew her as a different name. Sure, some might use their middle name instead of first name, we do that in English too. But if they can also pick what their FB name shows up as, then if my students want to then why not let them. Just my thought!

I have a hard enough time remembering their real name! Also, I don’t want students with “heritage” names to feel that their culture and naming practices are being “appropriated” by others. In an era where we are learning about identity formation in students, I tend to stay away from it. But if they have a name, like a mine, that lends itself to ‘Spanish pronunciation, I go for it.

Yes! This is definitely a case of appropriation. Don’t take their name without taking away their struggle.

I stopped giving my students Spanish or French names when a colleague who is of Latino heritage opened my eyes to many of the excellent reasons you mentioned for not doing it. I agree with your positive reasons for using real names for real relationships.

I understand your reasoning for not doing the Spanish names. It is a lot to memorize, and does get terribly confusing.

At the beginning of Spanish 1, after I’ve memorized students’ English names, I let them pick from the list of 100 most popular boy/girl names in Mexico. They can choose to be called a name on the list, or go by their English name. But at least they see this list. They see that there are names like Kevin, José, Brian, Emily, and Guadalupe. They see that not all names are “Mexican.” So stop shouting “cultural appropriation” at me.

The main reason I do the names is psychological. And I tell my students this. When someone calls me Profe, I respond “¿Sí?” When someone calls me Mrs. Smith, I respond “Yes?” Hearing my own “Spanish” name is my Pavlovian response to speak and respond in Spanish. And in the first year, when they haven’t been exposed to the language as much, I need that classical conditioning to condition them to speak Spanish when they talk to me. After that first year, they can continue to use their Spanish name or English name, I always let them decide.

I’ve read tons of responses from this thread and yesterday’s thread on “Spanish Teachers in the US,” and didn’t see anyone mention this.

So, maybe that’s why the tradition started. Back when “classical conditioning” were the educational buzzwords, some foreign language teacher figured out how to condition his students and got evaluated by their administrator as “most effective.” The idea got shared and other foreign language teachers hopped on the bandwagon.

So whether you give or don’t give foreign names, lay off of the people that do things differently from you. Educators already get enough flack from parents, politicians, and administrators. They don’t need any more flack from other educators.

I’ve never given Spanish names for all the reasons you mentioned. Totally agree with you. Nobody insisted I change my name when I moved to Spain. Besides, I can barely remember 100+ first and last name let alone a third!

I agree with you. I’ve never liked, nor used the idea of giving names. One of the reasons is also that just because I’m a native Spanish speaker doesn’t mean I’m called Maria, Esperanza, o Julieta. I agree it goes to further stereotypes. I’ve had many a student wonder how I can be a Spanish speaker being “so” white. I’m also a red headed Venezuelan. Totally outside of the stereotypes!

I have always done it because it was always done. In recent years, however, I have moved away from it. My interactions with native speakers have left me feeling slightly ridiculous. I remember kids from our French exchange program laughing at the name section in our text. I realised that the names are dated, much like an exchange student choosing the name Ethyl or Shirley. Skyping with a class in France where they introduced themselves by their French names left our correspondents slightly confused. Then I tried letting them use a names origin site, only to have my French students proudly introduce themselves as Jordan, Dax and Bruce (though calling a kid Bruce with a French accent, and that kid clearly doesn’t look like a Bruce is rather hilarious).

Honestly, for a person who found math class to be intimidating, difficult, not exactly up my alley of interest, and just generally a place I found uncomfortable, I think being called Hypotenuse or Pythagorean Theorem would’ve helped! Math was a scary, awful place, and I worry that languages may seem that way before students get to know a teacher or subject. I think that’s what most people mean when they say “Students think it’s fun.” Fun decreases intimidation and increases camaraderie. Both are crucial in an environment where we are fostering long-term communicative relationships between students and each other, and between students and teacher, so I can’t fault anyone for that justification.

I personally don’t use names very well, but I do let them choose them if they want. My colleague does it fully, though, and I think it’s amazing they way he uses them. Most importantly, it gives students a way to be okay feeling silly or not taking themselves too seriously, and makes the teacher/class approachable. This helps with known language learning inhibitors, such as fear of pronouncing “weird” sounds, fear of being wrong, and gives confidence for role-playing, trying new things, making language errors. It also helps students see a sense of humor in the teacher, and, if you do it the way my colleague does (having students choose descriptive words, refranes, inside jokes, etc., rather than only offering up Pedro or Margarita), it also helps them define their own identities, and shows that the teacher gives importance to the students’ own interpretations of their identities. I’ve had students come from his class with names like Deportista, Bailarina, Jinete, or “favorites,” like Canguro, Chipotle, Yucatán, and even names of personal heroes, like Ronaldo or Lionel. For those that want the name, it helps them express something, it can link them with aspects of Hispanidad that they wouldn’t otherwise choose to access, and it shows that the teacher cares. (For example, Deportista actually wasn’t that great at sports, but she played several and just loved them. He let her be known by being sporty, and having always idolized her sportier friends, she suddenly got to highlight that part of herself.)

So, even though I don’t see myself doing that great a job with it, I always let them keep names they liked and choose them if they want. Certainly doesn’t bother me if others don’t, though.

Me neither! I can barely remember their real names at the beginning of the year. I also don’t want them to feel self-conscious about their name.

I think that you make a lot of sense. I hadn’t thought about the whole students having Spanish names in Spanish class this way before, but now that you’ve made these points, I have to say I agree with you. Your also completely right about how the Spanish names given are just fake names. It’s not like if I went to a Spanish speaking country my name would automatically change from Tiffany to say Esmeralda. I think that while there may be no harm in assigning Spanish names and the students might think it’s fun, it’s still confusing and unnecessary and might just be better off being a thing of the past.

I have similar sentiments regarding the perpetuation of stereotypes. Whenever I tell any student that I speak Spanish, their first question is, “What is my name in Spanish?”. I modify pronunciation, but try to explain that their name is their name.

Now I want a math name.

I think it’s interesting to tell them but not to use them. Some names, like mine, were selected by my French-speaking parents because it was the same in each language.

Why not give them a list of Spanish names, and then give them the option of choosing one if they wish. Certain personalities enjoy choosing a Spanish name and will enjoy remembering it later in life.

Did you read the post?

I used to allow my students to pick French names as I thought it would entice them to learn French and allow them to develop a new personality. I stopped when I realized how important it was to get to know who they really were.

I stopped assigning names this year after eleven years of “Juan’s” and “Lupes”, the reason being I want the students to know that they can speak Spanish all the time in their own identity. Spanish isn’t a thing “José” speaks fifth hour, it’s a part of Joseph. Joseph is always Joseph, so Joseph can always use what Joseph knows. I was trained to assign names and it was bad training.

I used to let students pick a “Spanish name” in my rural, monochrome high school, then revised the practice two years after encountering interesting analysis by Ben Slavic and Bryce Hedstrom. Two points stood out: 1. In the first year especially, but also even in upper levels, as Slavic points out, students’ names can function as anchors of comprehensibility in an utterance. “Brady va al cine” is better than “Agustín va al cine” because students can understand the name, and then focus their attention on the other sounds in the sentence. They don’t have to also think through what “Agustín” means, or even that it is the name of their classmate Brady, they can just focus on the new language in smaller, contextually-understandable chunks. There is a similar practice used in Blaine Ray-style TPRS, in which he uses North American place names in the text to add interest and comprehensibility. (Boring, Oregon, is clearly understandable as a location; if we say, “Brady va a Boring Oregon, the student suddently has a ton of context for what “va a” might mean). As a teacher, I can vary the proncunciation of “Boring, Oregon” and “Brady” and perhaps gradually introduce more native-like pronunciation of these “English” words, as the students become more comfortable with the pronunciation system.

Sometime in semester 2 of the 1st year, once I know all students’ real names, or even after about a month or two of 2nd year, I do a lesson with students about “apodos” (nicknames) in different Spanish-speaking countries, as a common cultural practice. Often by this time, many students have already taken on an “apodo” through an authentic interaction. Slavic points out that nicknames arise naturally, and often reveal something important and unique about a specific kid and their relationships with the class and teacher. This is gold because for me, one of the most important things to communicate about in Spanish class, especially with adolescents, is their own identities, as they negotiate them in the context of the wider world.

I pass out a huge list of names from Spanish-speaking countries. This includes not just Christian/Spanish/Western Names, but also common indigenous-derived names like Atahualpa and Citlali, and we talk about linguistic communities within the Spanish-speaking world. We do some game-like pronunciation practice with the names, and we also talk about dynamics of cultural appropriation; what makes it “weird” to take names form another language community.

I also give students an edited version of Bryce Hedstrom’s list of “apodos” (His original is here: https://www.brycehedstrom.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/09/Nicknames-in-Spanish.pdf), and we do some more scavenger-hunt type games with them, again focussing on pronunciation, but also going into some cultural dimensions.

About 25% of students opt out completely, which I celebrate. The majority of students who choose a new name, choose an “apodo” rather than a “Spanish name”. Some of my Heritage students like to choose a new name or present an “apodo”, or will talk about nicknames that their family members have. Putting the renaming practice within the context of “nicknames” gives them a chance to help classmates navigate the meaning of the words and also to contribute their aesthetic sense for how the nicknames might sound to a native speaker from a specific language community.

I believe that adolescents’ identities are in flux and it’s important to help them find opportunities to explore. I will never simply give students Spanish names without spending some time introducing and exploring some problems of cultural appropriation that may come up. However, having them choose whether and what kind of name to use allows them to have a very personal experience with the concept of cultural appropriation and they get to make their choices in the context of their understanding of what may or may not be acceptable.

In my class, nicknames must be ACCEPTED, not just given. Reinforcing this idea that you don’t just get to give someone a mean nickname without their approval, makes a statement against bullying.

As an anglo with a name that is very difficult for Spanish-speakers to hear and pronounce (Reed), it has been a source of never-ending amusement and confusion throughout my years living in Spanish-speaking communities. Personally, I also just love giving nicknames to my friends and family as a way to show playfulness and affection; much of my desire to wade through the challenges in the practice is because I really enjoy calling kids by lots of different names. I tell them that I had a Spanish name once upon a time in HS Spanish class (Sergio), but they have to call me “don Sergio” if they want to use my nickname, and so we get to talk about the “don/doña” honorific, which doesn’t have a commonly used direct translation in English.

I am not sure if I will continue with the whole list of “Spanish names” this year and just go with “apodos,” but it’s definitely something to ponder. In the best-case scenario, we find an “apodo” that emerges from each students’ personality, but with large classes, this doesn’t always happen naturally, and kids will feel left out. That’s ok for a while while we wait for a true nickname to come out, but I put it on the calendar for February because it’s also a good time for a reminder for myself to see if I’m distributing my attention equally.

Thank you for taking the time to share your classroom practices with us! Lots of interesting ideas here!

I have been teaching for over 30 years and have always given my students Spanish names. They are asked to pick a name (or I pick one) that begins with the first letter/sound of their English name. I do this for 2 reasons: A) it gives them ownership of the language and b) they have always loved it! As the days pass after the semester starts, I hear stories that they forgot to write their English name in Math/Science/English class and wrote their Spanish name…HOW AWESOME! Years and years after I have taught them and we connect on FB or Insta, they always sign their names with their Spanish names. It’s a connection, a bond. So, frankly your post makes me sad, but I will wake up tomorrow and not remember it 😉 To each his own, right?

Pingback: White privilege of Names | SpanishPlans.org

Whatever anyone’s opinion about this…you have to agree that “Does your math teacher call you Hypotenuse?” is hilarious.

I can see both sides of the ethnic-name argument no matter which foreign language is being taught:

Name changes aren’t made in non-classroom contexts for foreign language use, or in classes for other kinds of subject. Very true; students should get used to a new language becoming part of their everyday selves, not just part of some persona adopted a few hours a week.. That said — if a student has a real name with a target-language parallel (George/Jorge, Alex/Alejandro, etc.) I’d allow but not require using the parallel name in class. (The analogy with math and history falls flat, though: no personal-name tradition is associated with the technical vocabulary of other fields, and few people would argue that assuming a famous-but-relevant person’s identity in class helps them learn ANY subject.)

People feel attached to their given names, including the pronunciation and spelling. Again, you make a valid point for most of us. (I personally hated my birth name since childhood, and changed the whole thing legally in my 20s; but I’m an exception to a VERY general rule!) Language learners do need to recognize and pronounce names used by “typical” (not stereotypical) native speakers; yet those same learners also need to get used to foreigners’ attempts at pronouncing a not-so-typical name. If both are that important, use role-played dialogues with suitably named characters; but don’t assign official “classroom names” that apply in every situation.

If a non-heritage speaker chooses an ethnic “classroom name” that’s not a parallel to his real one…even though that person might enjoy using the new name, heritage speakers may indeed feel as if others mean to mock snd stereotype their culture. Language courses are supposed to make a new culture understandable and approachable, not turn that culture into a tourist-trap caricature. Most of the time, “classroom names” create that unwanted effect, if a nicknaming tradition exists in the target culture (and the nickname actually fits the student!). referencing that instead seems best as you suggested. (“My name is Jane Doe, but my Mexican friends call me Geek Squad.”)

Great points! Thank you for adding to this discussion. Certainly lots of things to consider and be aware of.

hello, I am a latin boy who came to the UNITED STATES to learn English and I know that my name sounds strange but you friends can learn spanish

This article cracked me up. I don’t get name changes either. I took German but the same still applies.

Although if I took Spanish and I wish I did, I wouldn’t have minded being called the Spanish version of my name. That would make a little more sense to me.

When I originally replied to this thread 8.5 years ago (see Sharron Herring says:

August 18, 2012 at 8:00 pm), I did not even consider the conversation might continue for so long! It is fascinating to read each new reply that pops into my inbox.

At the time of my original post, I was teaching Spanish in a public school alternative ed program, with classes at the elementary, middle, and high school levels. Since that time, I taught 7th grade dual language for a couple of years, and I am now the librarian in a fully dual language, K-5 elementary school. Half of our incoming kinders come from predominantly Spanish speaking homes and the other half from English. I still allow students to choose their name; we just don’t talk about it as much. A couple of years ago, the majority of one first grade class chose nikcnames. Some were used by their families, some were English or Spanish equivalents to their given names, some were totally unrelated, like the little guy that wanted to be called John Wick all year long! Some were clever, like the Natilee who still likes to be called Eelitan. Names are deeply personal. Some people cling to their given name with no variations, others like something completely different.

I hope to teach middle and high school Spanish again. The program I taught in when I made my first reply is now housed next door to my current assignment, so who knows? Maybe I will be able to do both some day! If I do, I will still encourage my monolingual English students to take a Spanish-language name for the three reasons listed in my original post. If they really do not want to, I would be open to them not, but I will let them know I will likely end up pronouncing it differently in the course of speaking, even as a native Spanish speaker talking to them would pronounce it differently. It would be affected by the sound system of the language being spoken. If they are okay with that, I will be, too, but I suspect the majority will still enjoy choosing an alter-ego.